Uncle Sam and the Brickyard, 2022

fired Sam Wilson brickyard clay, steel, plexiglas

63″ x 35″ x 4″

2022 Uncle Sam and the Brickyard

Sam Wilson fired brick clay, found brick + pipe shards, steel from

Uncle Sam homestead site, soil from the artist’s yard

34" x 30 x 4"

2022

Study for Troy, Uncle Sam and the Brickyard and Your Story/ My Story, 2022

fired brick clay, found brick + pipe shards from Sam Wilson brickyard site (Troy, NY), soil from the artist's yard (Brentwood, MD), steel

34" x 30" x 4"

This work is a study for a commission that was completed in in 2022.

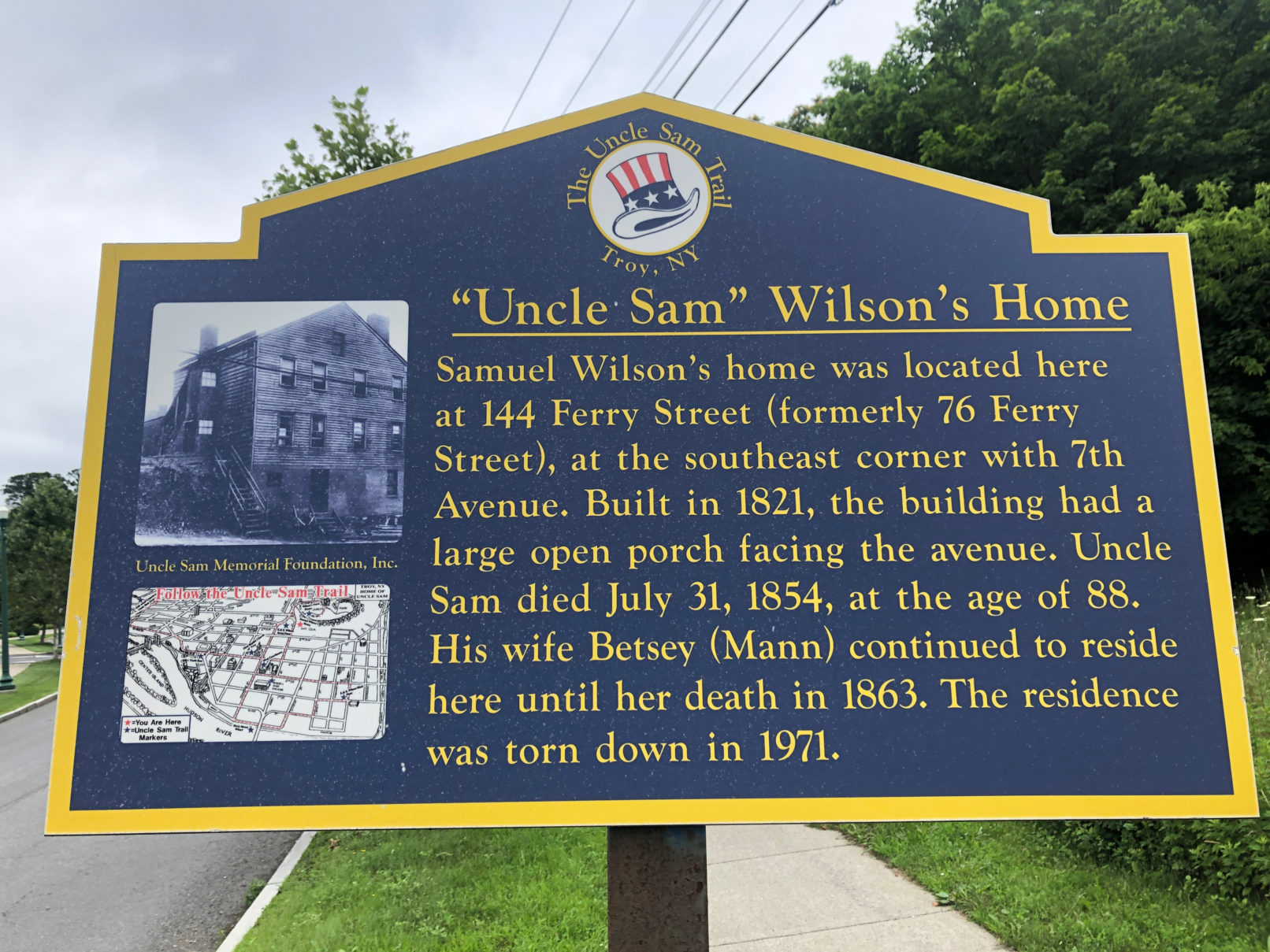

In 2021, I was commissioned by a Troy family to make a piece of art for their home. My practice involves digging local clays, soils and other materials for site specific work. I knew about the Hudson Valley’s brickyard history, and my clients informed me that THE Uncle Sam (Sam Wilson) had lived in Troy, and he and his brother had owned a brickyard there. So, the concept began…

This study, Troy, Uncle Sam and the Brickyard, is made from fired clay from Uncle Sam’s homestead, not far from his brickyard site. Visiting the site to dig clay, we also found brick shards emerging from the ground. That inspired an idea to create a map of Troy made from the fired brick clay, broken into shards. In this study, the broken shards are presented as if emerging from the ground.

I was interested in the story of the early days of the United States, when it was more common to see the earth as raw material to be used for gain with not much thought of over using or depletion. I was also interested in the story of American exceptionalism where two brothers without much means could rent a piece of land, and with a shovel and some good clay, start to build wealth and opportunity for themselves. But it’s important to remember that story is created at the expense of the Indigenous people whose land the colonists stole.

Two years later, I added a second part to the title of this piece... I added Your Story/ My Story as I began to understand the ways in which I find myself in this narrative. Finding clay in the landscape is exciting, and I haven’t always asked permission before taking some back to the studio. That is a small act of colonialism…wanting something and just taking it. When I created the study, I joined the shards together with soil from my own yard in Maryland. So the shards are from Uncle Sam’s property, which is now RPI’s, and the soil is from my property. But then, how did we come to own those respective properties? Working on this piece and this larger exhibition have really become an opportunity to think more about how I might have a more responsible and reciprocal relationship with land, and how I might bring some of this relationship and thinking into my artistic practice.

Sam Wilson fired brick clay, soil, found brick + pipe shards, steel

34" x 30 x 4

I'm thinking that’s what this image of a broken Uncle Sam brick shows… Soil scientists or anyone have ideas on this?

"Clay dogs are naturally occurring clay formations that are sculpted by river currents from glacially deposited blue-gray clay and then dried by the sun. They exhibit tremendous variety in shape and size, with some being simple and others having highly complex forms. They only occur in a few places in the world. Until recently, Croton Point along the Hudson River produced them, but the clay slope that produced the dogs was subsequently demolished to extend a park lawn.[1] Clay dogs were described in detail in an article by L. P. Gratacap, Opinions on Clay Stones and Concretions.[2]"

https://en.everybodywiki.com/Clay_dog

"In the Connecticut River Valley, these concretions are often called "claystones" because the concretions are harder than the clay enclosing them. In local brickyards, they were called "clay-dogs" either because of their animal-like forms or the concretions were nuisances in molding bricks."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concretion

By Devorah Lev-Tov, New York Times

May 21, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/21/nyregion/brickyards-nyc-hudson-valley.html?smid=url-share

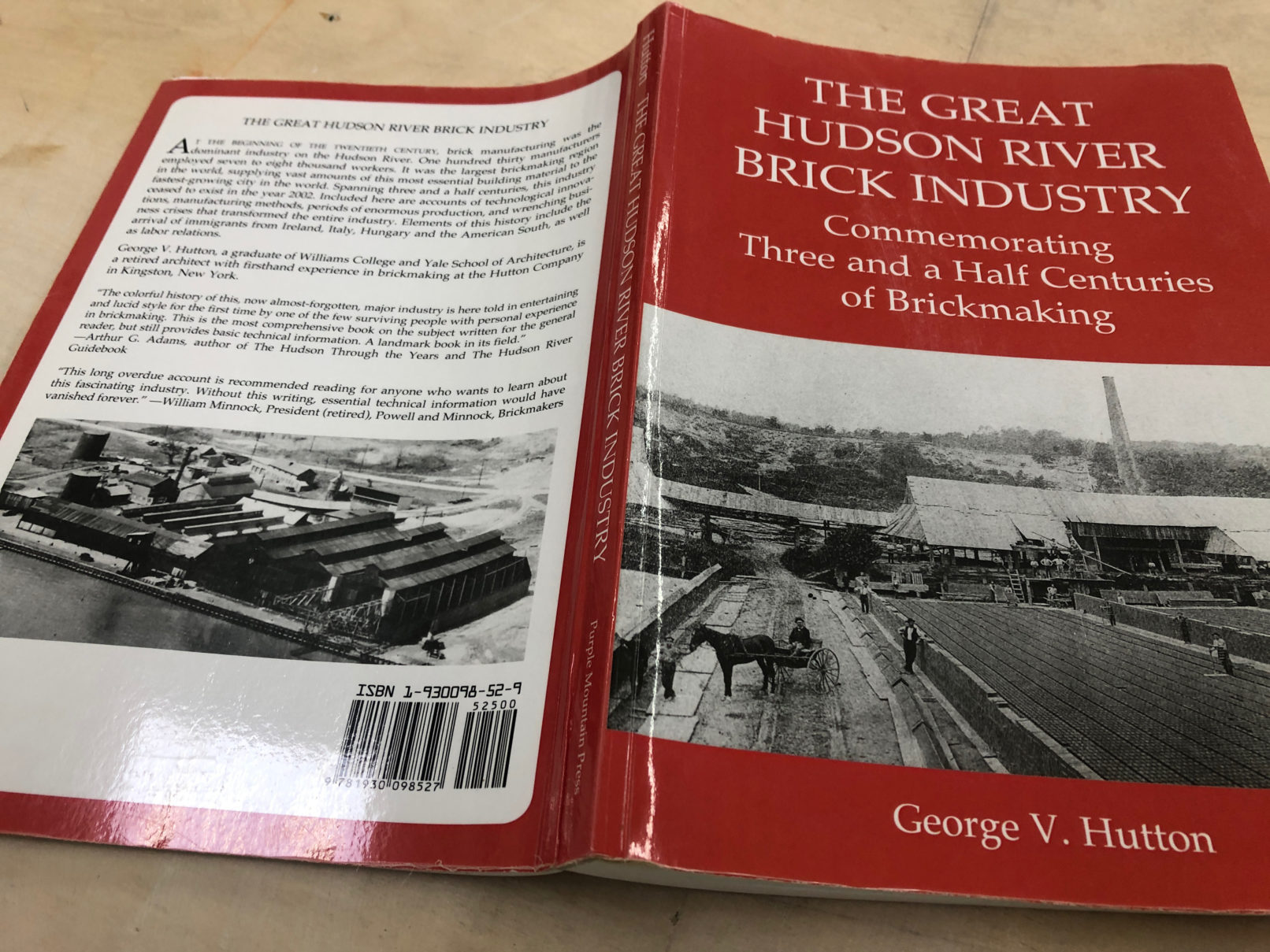

Hudson Valley bricks are an “inescapable presence” in New York City, George V. Hutton, a retired architect, wrote in his book about the once-booming industry.

Mr. Hutton, despite his clear bias — he was from a prominent brickmaking family in Kingston, N.Y. — was not wrong.

It’s fairly safe to assume that any brick building constructed between 1800 and 1950 includes some form of sediment from the banks of the Hudson River. The Empire State Building, the Museum of Natural History, the arches of the Brooklyn Bridge, Delmonico’s and countless residential buildings — including the Parkchester development in the Bronx and Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village in Manhattan — were all built from Hudson Valley bricks.

During the industry’s turn-of-the-century heyday, there were more than 135 brickyards along the riverbanks mining seemingly endless deposits of clay. In Ulster County alone, 65 brickyards were once in operation. In 1904, 226,452,000 bricks came out of Ulster County, according to its archives office, and most of them were sent directly to New York City....

Sam Wilson fired brick clay, found brick + pipe shards, steel from

Uncle Sam homestead site, soil from the artist’s yard

34" x 30 x 4"

2022

Study for Troy, Uncle Sam and the Brickyard and Your Story/ My Story, 2022

fired brick clay, found brick + pipe shards from Sam Wilson brickyard site (Troy, NY), soil from the artist's yard (Brentwood, MD), steel

34" x 30" x 4"

This work is a study for a commission that was completed in in 2022.

In 2021, I was commissioned by a Troy family to make a piece of art for their home. My practice involves digging local clays, soils and other materials for site specific work. I knew about the Hudson Valley’s brickyard history, and my clients informed me that THE Uncle Sam (Sam Wilson) had lived in Troy, and he and his brother had owned a brickyard there. So, the concept began…

This study, Troy, Uncle Sam and the Brickyard, is made from fired clay from Uncle Sam’s homestead, not far from his brickyard site. Visiting the site to dig clay, we also found brick shards emerging from the ground. That inspired an idea to create a map of Troy made from the fired brick clay, broken into shards. In this study, the broken shards are presented as if emerging from the ground.

I was interested in the story of the early days of the United States, when it was more common to see the earth as raw material to be used for gain with not much thought of over using or depletion. I was also interested in the story of American exceptionalism where two brothers without much means could rent a piece of land, and with a shovel and some good clay, start to build wealth and opportunity for themselves. But it’s important to remember that story is created at the expense of the Indigenous people whose land the colonists stole.

Two years later, I added a second part to the title of this piece... I added Your Story/ My Story as I began to understand the ways in which I find myself in this narrative. Finding clay in the landscape is exciting, and I haven’t always asked permission before taking some back to the studio. That is a small act of colonialism…wanting something and just taking it. When I created the study, I joined the shards together with soil from my own yard in Maryland. So the shards are from Uncle Sam’s property, which is now RPI’s, and the soil is from my property. But then, how did we come to own those respective properties? Working on this piece and this larger exhibition have really become an opportunity to think more about how I might have a more responsible and reciprocal relationship with land, and how I might bring some of this relationship and thinking into my artistic practice.

Sam Wilson fired brick clay, soil, found brick + pipe shards, steel

34" x 30 x 4

I'm thinking that’s what this image of a broken Uncle Sam brick shows… Soil scientists or anyone have ideas on this?

"Clay dogs are naturally occurring clay formations that are sculpted by river currents from glacially deposited blue-gray clay and then dried by the sun. They exhibit tremendous variety in shape and size, with some being simple and others having highly complex forms. They only occur in a few places in the world. Until recently, Croton Point along the Hudson River produced them, but the clay slope that produced the dogs was subsequently demolished to extend a park lawn.[1] Clay dogs were described in detail in an article by L. P. Gratacap, Opinions on Clay Stones and Concretions.[2]"

https://en.everybodywiki.com/Clay_dog

"In the Connecticut River Valley, these concretions are often called "claystones" because the concretions are harder than the clay enclosing them. In local brickyards, they were called "clay-dogs" either because of their animal-like forms or the concretions were nuisances in molding bricks."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concretion

By Devorah Lev-Tov, New York Times

May 21, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/21/nyregion/brickyards-nyc-hudson-valley.html?smid=url-share

Hudson Valley bricks are an “inescapable presence” in New York City, George V. Hutton, a retired architect, wrote in his book about the once-booming industry.

Mr. Hutton, despite his clear bias — he was from a prominent brickmaking family in Kingston, N.Y. — was not wrong.

It’s fairly safe to assume that any brick building constructed between 1800 and 1950 includes some form of sediment from the banks of the Hudson River. The Empire State Building, the Museum of Natural History, the arches of the Brooklyn Bridge, Delmonico’s and countless residential buildings — including the Parkchester development in the Bronx and Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village in Manhattan — were all built from Hudson Valley bricks.

During the industry’s turn-of-the-century heyday, there were more than 135 brickyards along the riverbanks mining seemingly endless deposits of clay. In Ulster County alone, 65 brickyards were once in operation. In 1904, 226,452,000 bricks came out of Ulster County, according to its archives office, and most of them were sent directly to New York City....

Artist's notes

This is the commissioned artwork for Troy, NY residents Steve and Andrea Hartman. This piece uses clay from Uncle Sam’s homestead and brickyard, formed into a map of Troy and presented as reassembled shards.

Uncle Sam, or Sam Wilson, was a real person, and he lived in Troy.

I worked with RPI engineers who own the site, soil scientists Olga Vargas and Steve Carlisle, and Troy historian Tom Carroll.

Tom Carroll shared:

“In February following [1789], the two brothers, Samuel and Ebenezer Willson, of Mason, New Hampshire, trudged across the hilly country to the little settlement. Samuel was then twenty-two years old and his brother twenty-seven. In the following summer they began making brick on the west side of Mount Ida, near the intersection of Sixth Avenue and Ferry Street. They made those with which the first brick building erected in the village was constructed,—the two-story dwelling, built in 1792, by James Spencer, on the northwest corner of Second and Albany streets. They also furnished the brick for the first courthouse and jail.”

—Arthur James Weise, M. A., Troy’s One Hundred Years, 1789-1889 (Troy, N.Y.: William H.Young, 1891), 31.

Steve Carlisle shared:

“As Tom Sanford [Rensselaer County Soil and Water Conservation District] indicated in our virtual meeting the clays are lacustrine deposits from Lake Albany. When high energy streams and meltwaters disgorged into the streams rapidly dissipating energy could no longer carry larger particles and they dropped out of suspension. Hence the gravel and sand deposits around Sand Lake, Averill Park and Wynantskill. Further out in Lake Albany where there was little energy to keep particles suspended the colloidal particles (clays) gradually wafted down to the lake bed. Surges in stream energy, summer versus winter, explain the layers or varves seen in the image where I scraped off some of the slough on the one photo. Lake Albany was dammed by the Harbor Hill Moraine which stretched from Staten Island to Brooklyn and Queens. When that moraine was breached Lake Albany drained, possibly in a cataclysmic fashion, and in its wake left the Hudson River and the narrows separating Staten Island from Queens.”